SRI LANKA HOLIDAYS:

Ancient Sri Lanka

The waterlords of ancient Sri Lanka

Quote Unesco Courier, Jan 1985: Dr. Ananda Guruge

"LET not a single drop of rain that falls on this island flow into the ocean without first serving humanity.' This was the governing principle of a massive water resources development programme undertaken by one of the greatest kings of ancient Sri Lanka, Parakramabahu I (1153-1186). The king's record was impressive. The Sri Lankan Chronicle, the Culavamsa which was written in the Buddhist canonical language Pali, enumerates his works both as a provincial ruler in western Sri Lanka and later as the monarch of the whole country: he either built or restored 163 major reservoirs (called "tanks' in Sri Lankan usage), 2,617 minor tanks, 3,910 irrigation channels, 328 stone sluices and 168 sluice blocks, besides repairing 1,969 breaches in embankments. Among the reservoirs he built was the tank at Polonnaruwa, called on account of its size the Sea of Parakrama. With an area of 3,000 hectares and an enclosing embankment fourteen kilometres long, it irrigated nearly 10,000 hectares.

The resulting improvement in the conservation and distribution of water brought about an expansion of cultivated land. Consequently, during his reign the production of rice increased to the point that Sri Lanka exported so much of it to neighbouring countries that the country is said to have become known as the granary of the east.

In executing this vast programe, King Parakrama Bahu the Great was fulfilling one of the most important royal duties laid down by tradition. The obligations of kings were conceived as serving the two-fold interests of the nation: the material and spiritual, expressed in Pali as loka-sasana-abhivuddhi. Under the first category came the two fundamental duties of defending the nation against external and internal threats to its security, and the conservation and management of water resources to promote rice cultivation. Included in the second category of duties was the sustenance of Buddhism through the promotion of monastic institutions and the construction of impressive edifices. Every Sinhala monarch who is rated great in history has excelled in all or at least two of these three functions.

King Mahasena, who constructed the Minneriya tank in the fourth century, was actually deified by the people, and in a temple on the lake bund he still receives homage from local cultivators who seek his help in growing successful crops. When the fifth-century king Dhatusena was asked by his rebellious son Kahsyapa to reveal where the royal treasures were hidden, he led his captors to Kala Weva, a lake with a circumference of ninety kilometres which he had constructed. Taking a handful of water, he said, "This, my friends, is the whole of my wealth.'

These constructions involved a very high level of technological knowledge and skill. Perennial rivers were dammed with stone barrages and diverted kilometres away from their courses. Seasonal streams were dammed in stages to form a series of reservoirs along the valleys. The earthen embankments of these reservoirs extended from a few hundred metres to fifteen kilometres and in some places were eighteen metres high. The Jaya-Ganga, an irrigation channel aptly called the Victory River, was a masterpiece of engineering ingenuity. Still functioning today, it is over eight kilometres long with a uniform width of twelve metres. To minimize silting and erosion of banks, its gradient for the first thirty kilometres is an imperceptible 1 in 10,000. It connects two river systems and maintains adequate water supplies in a series of interlinked tanks which irrigated over 46,000 hectares of rice-fields.

Though little is known of either their techniques or the tools they used, the skills of the ancient Sinhala engineers in hydrodynamics as well as surveying and levelling were of a very high order. The stone sluice gate with its control well, called in Sinhala the Biso-kotuva, was a remarkably effective apparatus which displays a full understanding of water under pressure. It regulated the speed and the quantity of water issued to the fields and thus protected both the channel and the fields from erosion and flooding. It also prevented a reservoir from being tapped to its last drop by eager cultivators in times of drought, to the detriment of the survival of man and beast. Similarly, a stone spill or flood escape was constructed to a required height, often some kilometres away from the sluice gate, to safeguard the embankments from the heavy pressure of suddent rain or flood water.

Many a modern engineer has been baffled by the sophisticated designs on which these reservoirs and channel systems were constructed. It is known that the Dutch engineers of the eighteenth century and their British counterparts in the nineteenth failed to understand the design of the giant tank near Mannar on the northwestern coast. Only in recent years, when the tank was restored in conformity with the original design, was it found that levelling by the unknown engineer of the past was vastly superior to that attempted by modern engineers.

The origin and early development of a Sinhalese science of water resources are not easy to trace. The earliest recorded instance of the construction of a reservoir dates to the founding of the Sinhala kingdom in the sixth century BC. But whatever the source of their technological knowledge, the Sinhalas won wide recognition for their skills in irrigation. Pliny's account of the Sri Lankan embassy to Rome in 45 AD to the court of the Emperor Claudius refers to the artificial lake near the capital, Anuradhapura. Though couched in mythological terms, the reference in the Kashmirian history Rajatarangani to Lankan experts who helped Jayapida to drain a lake sometime around the eighth century records a possible case of technical assistance.

A complex system of rules and regulations on the management of water has been operating in Sri Lanka since ancient times. Not only did it prescribe how water was to be distributed and used, it also assigned responsibilities for the upkeep of tanks and channels. Until driven to obsolescence by the advent of the monetary economy in recent times, these regulations were upheld through a process of co-operative self-help, and the tradition persists in remote villages.

The royal duty to develop water resources and thus provide life blood to rural Sri Lanka and its multi-faceted culture has been carried on by the Government of the country ever since political power was vested in national leaders in the 1930s. In a massive effort to regenerate the rural settlements of the Dry Zone in the north central and southeastern regions of the island, over 3,000 reservoirs of varying sizes together with their channel systems have been commissioned into service and vast stretches of new rice-fields have been brought under cultivation.

The Senanayaka-Samudraya (the Sea of Senanayake, so named in commemoration of the first Prime Minister of independent Sri Lanka, who was an indomitable pioneer in restoring ancient water resources and establishing new villages) vies with the Sea of Parakrama of 800 years ago. The most impressive effort in this direction is the current programme to divert Mahaveligana, the island's longest river. This multipurpose project which, besides producing electricity and controlling floods, will bring thousands of hectares under cultivation, symbolizes the persistent belief of Sinhalese that the glory of their nation lies in the village with its lake, rice-fields and temple.

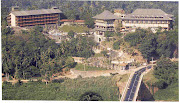

Photo: The great artificial lake of Anuradhapura in the north of Sri Lanka, with a monumental stupa, Ruwan Weli Seya, in the background. The kingdom of Anuradhapura (2nd century BC-10th century AD) created a remarkable irrigation system which was the basis of its prosperity.

Sunday, 7 September 2008

SRI LANKA HOLIDAYS: Ancient Sri Lanka

Posted by bunpeiris at 20:41

Labels: Sri Lanka Holidays

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment